Metabolic models#

Basics#

Definition 2 (flux)

(from [2]) The metabolic flux can be defined as the rate at which material is processed through a metabolic pathway. A reaction’s flux refers to the rate at which the biochemical reaction proceeds in a biological system. It’s a measure of how quickly reactants are being converted into products within a specific cellular context.

For insightful visualization that may help you with the concept of a flux, you may have a look here.

Genome-scale models#

Background: strain level#

In a simplified picture of balanced growth, all metabolic processes are balanced: the rate at which material flows into the cell matches the rate at which it is converted, which again matches the production rate of macromolecule precursors. In addition, we assume that these fluxes are constant, such that the whole metabolic network is in a ‘steady-state’. Taken together, we thus assume that the metabolic network can take up and produce external metabolites (e.g. extracellular metabolites and macromolecular precursors), but that all internal metabolites (“inside” the metabolic network) are mass-balanced, that is, for each of these metabolites, production and consumption cancel out.

Since each enzyme has a maximal catalytic rate (the \(k_{cat}\) value), a reaction flux will require a certain (minimal) amount of enzyme, which takes up cellular space; since cellular space is limited, fluxes cannot increase infinitely since there is always an upper bound on a weighted sum of reaction fluxes. This constraint implies compromises between different reaction fluxes: one flux can only be increased at the expense of others.

Definition 3 (Balanced growth)

Balanced growth is the average state of a cell in a cell bacterial population growing exponentially at the specific (constant) growth rate \( \mu ≥ 0 \), i.e. the amount of produced biomass per biomass per cell per unit of time.

The mathematical model:

variables to describe: the metabolic fluxes in steady-state metabolism,

constraints to apply: the balance of production and consumption of all internal metabolites

Importantly, the model will be able to describe compromise: for example, with a given carbon influx and assuming mass balance, the carbon atoms can either be used to generate energy or biomass; if one function increases, the other one goes down.

To obtain realistic predictions, we may introduce additional constraints, for example known flux directions or experimentally measured uptake rates.

All this information will not suffice to predict metabolic fluxes precisely, but it allows us to narrow down the possible flux distributions.

The mass-balance constraints in the previous equation, combined with the property that \(v_i^+\) , \(v_i^- ≥ 0\) can be expressed in the form

where:

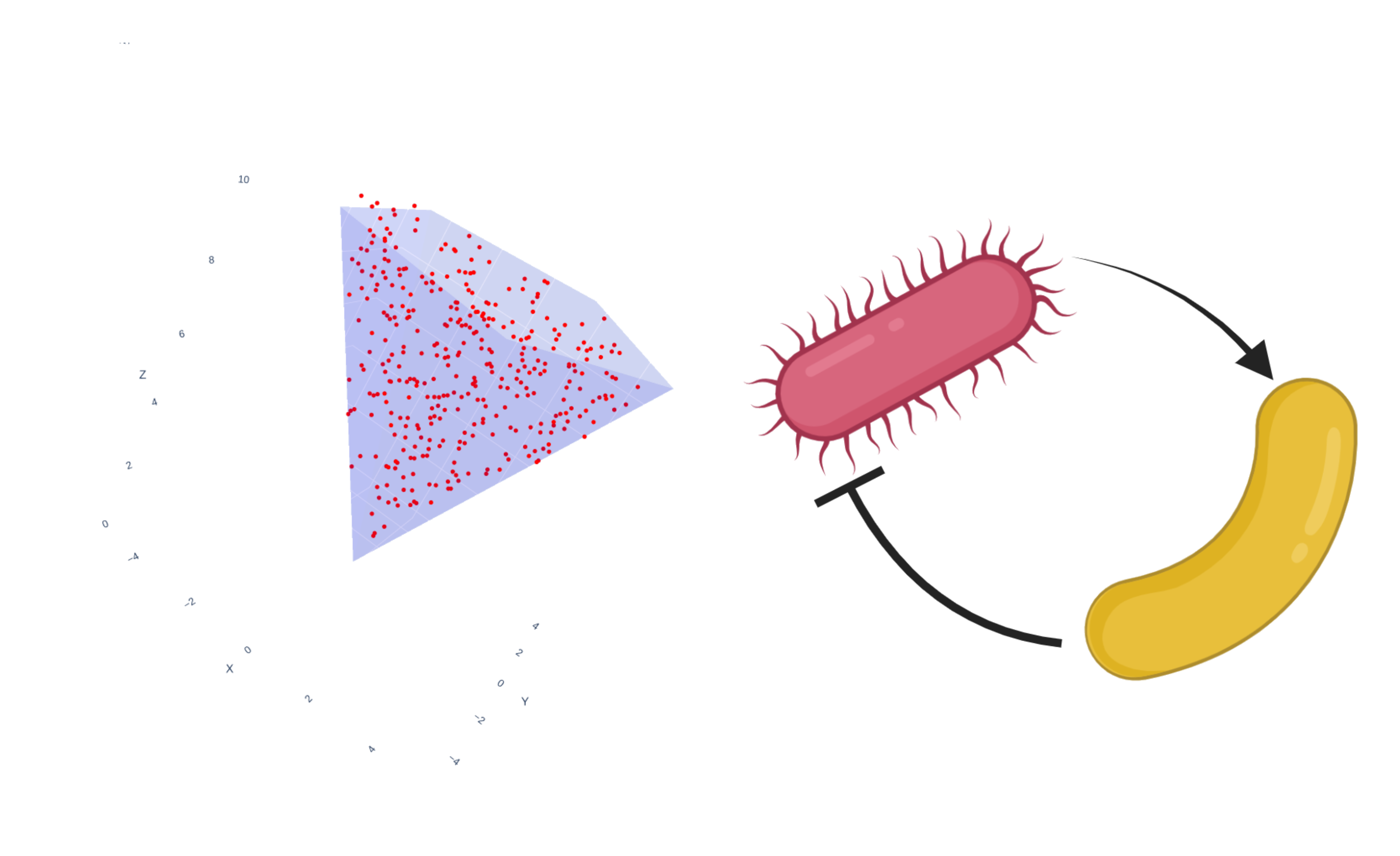

The set of constraints on (\(v^+\) , \(v^−\) ) define a polyhedral cone and since they are non-negative, the cone is also pointed, meaning it contains no complete line and the zero vector is the only vertex (extreme point) of the cone.

The space of solutions that satisfies is called the flux cone.

Background: community level#

Constraint-based modeling of microbial communities is more complicated compared to single organisms and this is because of the interdependencies between the metabolic objectives of microorganisms in the community. This is reflecting the fact that the metabolic performance (fitness) of each organism is dependent on all others, either directly or indirectly.

the community metabolic state in a constraint-based stoichiometric model of the microbial community would have to emerge from the multi-objective optimization of each of those performances, taking into account trade-offs and possibly allowing for suboptimal strategies

Hence, a nonlinear multi-objective optimization perspective appears most appropriate

However, the commonly used community FBA (cFBA) does not consider the above and makes use of a much simpler framework, considering the microbial community under study being in a balanced growth.

Definition 4 (Balanced growth at the community level)

Moving from the strain to the community level, balanced growth definition extends. In this case, all metabolites (intra- and extracellular) to attain a steady state level [3]. This means that **species grow exponentially, but their total biomass and proportions remain constant.

However, such a case should not be considered as a given for what really goes on in real-world communities, since by definition, the community balanced growth requires dependencies between species.

Yet, these dependencies are dynamic and can also be negative; cFBA suffers in both these cases.

Important

Balanced growth at the community level is not the only option

A multi-level and multi-objective optimization formulation to properly describe trade-offs between individual vs. community level fitness criteria.

OptCom interrelate the objectives of individual organisms [4].

Metabolic models with cobrapy#

Boundary reactions#

As described in the cobrapy ReadTheDocs, boundary reactions are

unbalanced pseudo reactions, that means they fulfill a function for modeling by adding to or removing metabolites from the model system but are not based on real biology.

An exchange reaction is a reversible reaction that adds to or removes an extracellular metabolite from the extracellular compartment.

A demand reaction is an irreversible reaction that consumes an intracellular metabolite.

A sink is similar to an exchange, but specifically for intracellular metabolites, i.e., a reversible reaction that adds or removes an intracellular metabolite.

An interesting issue on the topic.

Groups#

By group.kind one may get the kind of group.

Members of a classification group should have an is-a relationship to the group (e.g. member is-a polar compound, or member is-a transporter).

Members of a partonomy group should have a part-of relationship (e.g. member is part-of glycolysis).

Members of a collection group do not have an implied relationship between the members, so use this value for kind when in doubt (e.g. member is a gap-filled reaction, or member is involved in a disease phenotype).

Kinetic models#

Kinetic models are typically formulated as a set of deterministic ordinary differential equations (ODEs).

Definition 5 (kinetic variables)

kinetic parameters:

\(k_{cat}\): It is the maximum rate at which an enzyme can catalyze a specific reaction when it is saturated with substrate. It indicates the number of substrate molecules converted into product per enzyme molecule per unit time under optimal conditions. In simpler terms, it reflects how fast an enzyme can convert substrate into product.

\(K_M\):

\(\frac {k_{cat}}{ K_M}\):

Assumptions used in the formulation of biological network models

Assumption |

Description |

|---|---|

Continuum assumption |

Do not deal with individual molecules, but treat medium as a continuum |

Finer spatial structure ignored |

Medium is homogeneous |

Constant-volume assumption |

V is time-invariant, \(\frac {dV} {dt} = 0\) |

Constant temperature |

Isothermal systems; Kinetic properties a constant |

Ignore physico-chemical factors |

Electroneutrality and osmotic pressure can be important factors, but are ignored |

The stoichiometric matrix (\(S\)) represents the reaction topology of a network. For an overview on its characteristics see [5].

Definition 6 (gradient matrix)

(from [5]) Each link in a reaction map has kinetic properties with which it is associated. The reaction rates that describe the kinetic properties are found in the rate laws, \(v(x; k)\), where the vector \(k\) contains all the kinetic constants that appear in the rate laws. Ultimately, these properties represent time constants that tell us how quickly a link in a network will respond to the concentrations that are involved in that link.

The reciprocal of these time constants is found in the gradient matrix \(G\), whose elements are

These constants may change from one member to the next in a biopop- ulation, given the natural sequence diversity that exists. Therefore, the gradient matrix is a genetically determined matrix. Two members of the population may have a different \(G\) matrix.

Mathematically speaking, \(G\) has several challenging features. Unlike the stoichiometric matrix, its numerical values vary over many orders of magnitude. Some links have very fast response times, while others have long response times. The entries of \(G\) are real numbers and, therefore, are not “knowable.” The values of \(G\) will always come with an error bar associated with the experimental method used to determine them. It has though, the same sparsity properties as the matrix \(S\).

Definition 7 (Jacobian matrix)

\(S\) gives us network structure and \(G\) gives us kinetic parameters of the links in the network. Their product, the Jacobian matrix (\(J\)) gives us the network dynamics.

Observation 1

Fluxes are measured in moles per unit of time per cell.

Definition 8 (MASS model)

a metabolic network model that explicitly accounts for the regulatory enzymes, and all their bound states, as components in the network. The result is a data-driven process for constructing mass action stoichiometric simulation (MASS) models that are based on mapping top-down omics data onto bottom-up network reconstructions.

For more about MASS models you may check Palsson’s book on dynamic models [6] and one of his papers [7]

Enzymatic constraints#

adssa

Community models#

Here we keep some insight on how to build such models.

From cite{wedmark_hierarchy_2024}

Quote!

The community model was made by merging the individual models into a new model and connecting them through exchanged metabolites in a shared compartment. Specifically, the exchange reactions of the individual models were connected to the shared metabolites and new exchange reactions between the shared compartment and the environment were created, allowing the inter microbial and environmental exchanges described in Fig 1A of Taffs et al. [26]. A pseudo-metabolite consisting of equal shares of biomass from each of the individual microbes was constructed and used as the substrate in a community biomass reaction, thus requiring balanced growth of all three microbes.